PlaneSpottingWorld welcomes all new members! Please gives your ideas at the Terminal.

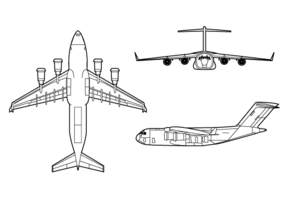

C-17 Globemaster III

| C-17 Globemaster III | |

|---|---|

| Unlike most strategic airlifters, the C-17 Globemaster III excels at operating from rough or improvised landing strips. | |

| Type | Strategic airlifter |

| Manufacturer | McDonnell Douglas/Boeing |

| Maiden flight | 15 September 1991 |

| Introduced | 14 July 1993 |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | United States Air Force Royal Air Force Royal Australian Air Force Canadian Forces |

| Number built | at least 180[1] |

| Unit cost | est. $180 million[1] |

| Developed from | McDonnell Douglas YC-15 |

The Boeing (formerly McDonnell Douglas) C-17 Globemaster III is a strategic airlifter manufactured by Boeing Integrated Defense Systems, and operated by the United States Air Force, the Royal Air Force and the Royal Australian Air Force. It has also been selected by the Canadian Forces with a planned 2007 delivery.[2] NATO also has plans to acquire the airlifter.

Contents

Mission

The C-17 Globemaster III is the newest purpose-built cargo aircraft to enter the United States and Western air forces. It is capable of rapid strategic delivery of troops and all types of cargo to main operating bases or directly to forward bases in the deployment area. This aircraft is also capable of performing tactical airlift and airdrop missions when required, as well as aeromedical evacuation. The inherent flexibility and performance of the C-17 force improves the ability of the total airlift system to fulfill the worldwide air mobility requirements of the United States.

The ultimate measure of airlift effectiveness is the ability to rapidly project and sustain an effective combat force close to a potential battle area. In recent years the size and weight of U.S. mechanized firepower and equipment have grown, which has significantly increased air mobility requirements, particularly in the area of large or heavy outsize cargo. As a result, newer and more flexible airlift aircraft such as the C-17 are needed to meet potential armed contingencies, peacekeeping or humanitarian missions worldwide.

History

In the 1970s, USAF began looking for a replacement for the C-130 Hercules tactical airlifter. The Advanced Medium STOL Transport (AMST) competition was held, with Boeing proposing the YC-14, and McDonnell Douglas proposing the YC-15. Despite both entrants exceeding specified requirements, the AMST competition was cancelled before a winner had been selected.

By the early-1980s, the USAF found itself with a very large, but aging fleet of C-141 Starlifters. Some of the C-141s had major structural problems as a result of heavy use. Compounding matters, USAF historically never possessed sufficient strategic airlift capabilities to fulfill its airlift requirements. In response, McDonnell Douglas elected to develop a new aircraft using the YC-15 as the basis. McDonnell Douglas won the contract to build its proposed aircraft, by then designated the C-17A Globemaster III, on August 28, 1981. The new aircraft differed in having swept wings, increased size, and more powerful engines. This would allow it to perform all work performed by the C-141, but to also fulfill some of the duties of the C-5 Galaxy, so that the C-5 fleet would be freed up for larger, more outsize cargo.

Development continued until December 1985 when a full-scale production contract was signed. Its maiden flight was on September 15, 1991 from the McDonnell-Douglas west coast plant in Long Beach, California. This aircraft (T-1) and five more production models (P1-P5) participated in extensive flight testing and evaluation at Edwards AFB. The first C-17 squadron was declared operational by the U.S. Air Force in January 1995. Two years later McDonnell Douglas merged with its former competitor, Boeing.

On August 18, 2006 Boeing announced it is telling suppliers to stop work on parts for uncommitted C-17s. This move is the first step in shutting down production if no new plane orders were received from the US Government.[3] However, just one month later on September 21, a House and Senate conference committee approved a US$447 billion defense bill for 2007, that includes $2.1 billion for 10 additional C-17s – which is seven more planes than either chamber originally approved in separate versions of their funding language. However, this extends the life of the program only 1 additional year, to 2010. As of October 6, 2006, Boeing executives have not yet rescinded their "stop work" announcement to suppliers.

The decision to authorize additional C-17 purchases followed intense lobbying by the Chicago-based company, as well as politicians from California, where the plane is made, and Missouri, where Boeing's defense business is based.[4]

C-17A production is planned to end in 2009 unless Boeing receives a follow-on order in sufficient time to allow the production pipeline to remain in operation. If such an order is placed, Boeing would begin C-17B production in 2010. The proposed C-17B would be capable of landing on sandy beaches and other areas off-limits to the C-17A.[5]

On March 2 2007, Boeing announces C-17 production line may end in mid-2009 due the lack of U.S. government and new international orders [6]

Features

The C-17 is powered by four fully reversible, F117-PW-100 turbofan engines (the Department of Defense designation for the commercial Pratt and Whitney PW2040, currently used on the Boeing 757). Each engine is rated at 40,440 lbf (180 kN) of thrust. The thrust reversers direct the flow of air upward and forward. This facilitates a decreased rate of ingestion of foreign object debris (FOD) as well as reverse thrust capable of backing the aircraft. Additionally, the C-17's thrust reversers can be used at idle-reverse in flight for added drag in maximum-rate descents.

The aircraft is operated by a minimum crew of three (pilot, copilot, and loadmaster). Cargo is loaded onto the C-17 through a large aft door that accommodates both rolling stock (vehicles, trailers, etc.) and palletized cargo. The cargo floor has rollers (used for palletized cargo) that can be flipped to provide a flat floor suitable for rolling stock. One of the larger pieces of rolling stock that this aircraft can carry is the 70-ton M1 Abrams tank.

Maximum payload capacity of the C-17 is 170,900 lb (77,500 kg), and its maximum gross takeoff weight is 585,000 lb (265,350 kg). With a payload of 160,000 lb (72,600 kg) and an initial cruise altitude of 28,000 ft (8,500 m), the C-17 has an unrefueled range of approximately 2,400 nautical miles (4,400 km) on the first 71 units, and 2,800 nautical miles (5,200 km) on all subsequent units, which are extended-range models with an additional fuel tank in the center wing box. These units are informally referred to by Boeing as the C-17 ER.[7] Its cruise speed is approximately 450 knots (833 km/h) (.74 Mach). The C-17 is designed to airdrop 102 paratroopers and equipment.

The C-17 is designed to operate from runways as short as 3,000 ft (900 m) and as narrow as 90 ft (27 m). In addition, the C-17 can operate out of unpaved, unimproved runways (although this is rarely done due to the increased possibility of damage to the aircraft). The thrust reversers can be used to back the aircraft and reverse direction on narrow taxiways using a three-point (or in some cases, multi-point) turn maneuver.

Operators

United States Air Force

The first production model was delivered to Charleston Air Force Base, S.C., on July 14, 1993. The first squadron of C-17s, the 17th Airlift Squadron, was declared operationally ready on January 17, 1995.

The Air Force originally programmed to buy a total of 120 C-17s, with the last one being scheduled for delivery in November 2004. The fiscal 2000 budget funded another 14 aircraft for Special Operations Command. Basing of the original 120 C-17s was at Charleston AFB, South Carolina, McChord Air Force Base, Washington (first aircraft arrived in July 1999), Altus AFB, Oklahoma, and the 172d Airlift Wing at Jackson, Mississippi. Basing of the additional 13 aircraft went to McGuire Air Force Base, New Jersey, Elmendorf Air Force Base, Alaska, Hickam Air Force Base, Hawaii, Dover Air Force Base, Delaware and Travis Air Force Base, California. An additional 60 units were ordered in May of 2002. In FY 2006, Eight C-17s were delivered to the 452d Air Mobility Wing at March ARB, California. These C-17s are the only ones strictly under direct command of the Air Force Reserve Command.

The C-17 was used to deliver military goods and humanitarian aid during Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan as well as Operation Iraqi Freedom in Iraq. On March 26, 2003, fifteen USAF C-17s participated in the biggest combat airdrop since the United States invasion of Panama in December, 1989: the night-time airdrop of 1,000 paratroopers from the 173rd Airborne Brigade occurred over Bashur, Iraq. It opened the northern front to combat operations and constituted the largest formation airdrop carried out by the United States since World War II.

The USAF has also lent its C-17s to allies to assist in transport of military equipment. This included the transportation of Canadian armored vehicles to Afghanistan in 2003 and the movement of Australian forces to East Timor in 2006. In late September and early November 2006, USAF C-17s flew 15 Canadian Forces Leopard C2 tanks from Kyrgyztan into Kandahar AF in support of the Afghanistan NATO mission.

There has been debate regarding follow-on orders for the C-17, with the Air Force requesting line shutdown, and members of Congress attempting to reinstate production. Furthermore, in FY2007, the Air Force requested $1.6 billion to deal with what it termed "excessive combat use" on operational airframes.[8]

Royal Air Force

Boeing has actively marketed the C-17 to many European nations including Belgium, France, Spain and the United Kingdom. Of these, the UK was always seen as the most likely customer given its increasingly expeditionary military strategy and global commitments. The Royal Air Force has established an aim of having interoperability and some weapons and capabilities commonality with the United States Air Force. The UK's 1998 Strategic Defence Review identified a requirement for a strategic airlifter. The Short-Term Strategic Airlift (STSA) competition commenced in September of that year, however tendering was cancelled in August 1999 with some bids identified by ministers as too expensive (including the Boeing/BAe C-17 bid) and others unsuitable.[9] The project continued, with the C-17 seen as the favourite.[9] The UK Defence Secretary, Geoff Hoon, announced in May 2000 that the RAF would lease four C-17s at an annual cost of £100 million[8] from Boeing for an initial seven years with an optional two year extension. At this point the RAF would have the option to buy the aircraft or return them to Boeing. The UK committed to upgrading the C-17s in line with the USAF so that in the event of them being returned to Boeing the USAF could adopt them.

The first C-17 was delivered to the RAF at Boeing's Long Beach facility on May 17, 2001 and flown to RAF Brize Norton by a crew from No. 99 Squadron which had previously trained with USAF crews to gain competence on the type. The RAF's fourth C-17 was delivered on August 24, 2001. The RAF aircraft were some of the first to take advantage of the new centre wing fuel tank.

The RAF declared itself delighted with the C-17 and reports began to emerge that they wished to retain the aircraft regardless of the A400M's progress. Although the C-17 fleet was to be a fallback for the A400M, the UK announced on July 21, 2004 that they have elected to buy their four C-17s at the end of the lease, even though the A400M is moving towards production. They will also be placing a follow-on order for one aircraft, though there may be additional purchases later.[10] While the A400M is described as a "strategic" airlifter, the C-17 gives the RAF true strategic capabilities that it would not wish to lose, for example a maximum payload of 77,000 kg compared to the Airbus' 37,000 kg.[8]

The Ministry of Defence (MoD) announced on August 4, 2006 that they had ordered an additional C-17 and that the four aircraft on lease will be purchased at the end of the current contract in 2008. The fifth aircraft is due to be delivered in 2008. Due to fears that the A400M may suffer further delays, the MoD is planning to acquire three more C-17s (for a total of eight) for delivery in 2009-2010, provided that the U.S. Air Force places a follow-on order extending through the same time period.[11]

In RAF service the C-17 has not been given an official designation (e.g. C-130J referred to as Hercules C4 or C5) due to its leased status, but is referred to simply as the C-17. Following the end of the lease period the four aircraft will assume an RAF designation, most likely "Globemaster C1."

Royal Australian Air Force

In late 2005, it was revealed that the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) was considering the purchase of four C-17s or eight A400Ms for strategic transport. Minister for Defence Robert Hill stated that the Australian Defence Force was considering such aircraft due to the limited availability of strategic airlift aircraft from partner nations and air freight companies. The C-17 was considered to be the favorite as it was a "proven aircraft" and was already in production. One major requirement from the RAAF was the ability to airlift the Army's new M1 Abrams main battle tanks; another requirement was immediate delivery. Though unstated, commonality with the USAF and the United Kingdom's RAF was also considered advantageous. The aircraft for the RAAF were ordered directly from the USAF production run, and are identical to American C-17 even in paint scheme, the only difference being the national markings. This has allowed delivery to commence within nine months of commitment to the program.[12]

On March 2, 2006 the Australian Government announced the purchase of three aircraft and one option with an entry into service date of 2006.[8] The Australian Government's 2006-07 budget (May 2006) included funding of A$2.2billion to fund the purchase of three or four C-17s and related spare parts and training equipment.[13] In July 2006 a fixed price contract was awarded to Boeing to deliver four C-17s for US$780m (AUD$1bn). Work on the aircraft will be completed in phases, with the first C-17 delivered to Australia in December 2006 and follow on deliveries continuing through to February 2008.[14]

The Royal Australian Air Force took delivery of its first C-17 in a ceremony at Boeing's plant at Long Beach, California on 29 November 2006.[15] Several days later the aircraft flew from Hickam Air Force Base, Honolulu, Hawaii to Defence Establishment Fairbairn, Canberra, arriving on December 4, 2006. The aircraft was formally accepted in a ceremony at Fairbain shortly after arrival.[16] They are operated by No. 36 Squadron based out of RAAF Base Amberley, Queensland.

Future and potential operators

Canadian Forces

Canada has a long-standing need for strategic airlift for humanitarian and military operations around the world. The Canadian Forces (CF) have followed the pattern of the Luftwaffe in using rented Antonovs and Ilyushins for many of their needs, including deploying the Disaster Assistance Response Team (DART) to tsunami-stricken Sri Lanka in 2005. The CF was forced to rely entirely on leased An-124 Condors for a deployment to Haiti in 2003, as well as a combination of leased Condors and USAF C-17s for moving heavy equipment into Afghanistan.

The Canadian Forces Future Strategic Airlifter Project has studied alternatives since 2002, including long-term leasing arrangements. The assumption was that the military was pushing for the C-17 even though the outright purchase of even a small number was considered beyond the reach of the current defence budget.[17] The current Conservative Government promised during the January 2006 federal election campaign to purchase three or four strategic airlifters, which was thought to be thinly veiled reference to the C-17.[18]

Minister of National Defence Gordon O'Connor announced on June 29, 2006, that the CF would acquire four strategic lift aircraft at a cost of C$1.8 billion (US$1.6 billion).[19] On July 5 the Government issued a notice on the MERX purchasing system that it intended to negotiate directly with Boeing for the purchase of four aircraft.[20] This supply notice declared the government's intention to purchase the C-17 unless another supplier could demonstrate that they meet the mandatory requirements prior to August 4, 2006.

On February 1, 2007 the Canadian government awarded the contract for four C-17s for delivery beginning in August 2007.[21] Similar to Australia, Canada will be granted airframes originally slated for the U.S. Air Force, to accelerate delivery.[22] To reduce costs, the Canadian government is purchasing the airframes from Boeing, while purchasing all the Pratt & Whitney engines from a USAF supply. This emulates the USAF approach developed in recent years to split the purchase in order to reduce costs from integrating the engines with the airframe.[citation needed]

NATO

The Royal Danish Air Force signed a letter of intent to purchase C-17s on July 19, 2006 at the 2006 Farnborough Air Show to participate in the joint purchase and operation of C-17s within NATO, a program called the Strategic Airlift Capability.[23] A further letter of intent was announced on September 12, 2006 that includes Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia and the United States to be part of a larger NATO joint purchase.[24] Later on, NATO countries Hungary and Norway, as well as Partner country Sweden also signed the Letter of Intent.[25] The purchase would encompass three or four C-17s, likely operating from Germany in the same fashion as the NATO AWACS aircraft.[26] The AWACS aircraft are jointly manned by crew from various NATO countries. NATO has 17 E-3 Sentry aircraft, stationed at Geilenkirchen in Germany.

German Luftwaffe

The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and resultant tsunamis placed a strain on the global strategic airlifter pool. The performance of the C-17 in USAF and RAF service has led to Germany considering 2-4 C-17s for the Luftwaffe in a Dry Lease arrangement, at least until the A400M is available in 2009. Germany's former Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer stated in the German news magazine Der Spiegel that the government needed its own organic strategic transport capability to be able to respond to disasters in a better manner than it was able to for this incident. During the tsunami relief effort, Germany tried to acquire transport through its usual method of wet leasing Antonov airlifters via private companies, but found to its dismay that there were no available aircraft. While the stated goal of a C-17 lease would be to last until the A400M's arrival, the Luftwaffe may elect to retain them.[27] Luftwaffe acquired meanwhile airlift capacity through the NATO SALIS contract.[28]

Swedish Armed Forces

The Swedish Armed Forces have in a spring 2006 budget proposal identified a need for a strategic airlift capability for use with the EU Nordic Battle Group led by Sweden. The battle group is intended to be placed on rapid deployment alert on January 1, 2008 which thus necessitates a rapid decision on what type of airlift assets will be employed to move the battlegroup within given weight and time constraints should it be needed. Repeated reports in the Swedish media suggest that the Armed Forces are lobbying hard for the airlift requirement to be satisfied with the purchase of two C-17 aircraft at a total cost of 4 billion SEK (roughly 10% the anual defence budget, 2006-2009, 37 billion SEK).[citation needed]

A request for information (now removed) published on the Swedish Defense Materiel Administration website included the following information: "Therefore, during this period of time, Sweden must have a capability to deploy, within 30 days, the Battle Group, including 6000 tons of military equipment, from Sweden to the area of responsibility 4000 NM away. Around ¼ of the cargo is oversized."

Sweden has now signed a LOI to join NATO's Strategic Airlift Capability (NSAC).[29]

Japan Air Self-Defense Force

In September, 2006, General Paul V. Hester, head of the United States Pacific Air Forces, stated that Japan was considering purchasing C-17s to equip the Japan Air Self-Defense Force.[30]

Commercial operators

In the mid-1990s, McDonnell Douglas began to market the C-17 to commercial civilian operators, under the name MD-17.[1]. Due to its high projected fuel, maintenance and depreciation cost for a low-cycle military design in commercial service, as well as a limited market dominated by the An-124 and A300-600ST, very little interest was expressed. After McDonnell Douglas merged with Boeing, the program was renamed BC-17.[2] However, the aircraft has had no takers.

Units operating the C-17

United States Air Force

Inventory: 71 C-17, 85 C-17 ER (+42 C-17 ER on order) (as of September 9, 2006)

- Altus AFB

- Charleston AFB

- Hickam AFB

- March ARB

- 452d Air Mobility Wing, Air Force Reserve Command

- McChord AFB

- McGuire AFB

- Allen C. Thompson Field ANGB

- Travis AFB

Royal Air Force

Inventory (as of February 2007): 4 C-17ER (+1 C-17 ER on order with a possible 3 or 4 C-17 ER's ordered in 2008/2009.)

Royal Australian Air Force

Inventory (as of February 2007): 1 C-17 ER, 3 C-17 ER on order (to be delivered in 2007-2008)

Canadian Forces

Inventory (as of February 2007): 4 C-17 ER on order (to be delivered from August 2007-2008); will use designation of C-177 Globemaster III within the Canadian Armed Forces.[citation needed] These aircraft will be stationed under8 Wing Trenton/CFB Trenton

Specifications (C-17)

General characteristics

- Crew: 3: 2 pilots, 1 loadmaster

- Capacity:

- 102 troops or

- 36 litter and 54 ambulatory patients

- Payload: 164,900 lb (74,785 kg) of cargo distributed at max over 18 463L master pallets or a mix of palletized cargo and vehicles

- Length: 174 ft (53 m)

- Wingspan: 169.8 ft (51.75 m)

- Height: 55.1 ft (16.8 m)

- Wing area: 3,800 ft² (353 m²)

- Empty weight: 282,500 lb (128,100 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 585,000 lb (265,000 kg)

- Powerplant: 4× Pratt & Whitney F117-PW-100 turbofans, 40,440 lbf (180 kN) each

- * Zero fuel weight: 77,400 lb (35,108 kg)

- Fuel capacity: 35,546 US gal (134,556 L)

Performance

- Maximum speed: 450 knots (520 mph, 830 km/h)

- Cruise speed: 390 knots (450 mph, 720 km/h)

- Range: 2,400 nm (2,800 mi, 4,400 km)

- Service ceiling: 45,000 ft (13,700 m)

- Max wing loading: 150 lb/ft² (750 kg/m²)

- Minimum thrust/weight: 0.277

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Aerospaceweb.org | Aircraft Museum - C-17 Globemaster III

- ↑ Boeing has $8B military contract, company says

- ↑ Boeing preparing to end C-17 production

- ↑ Boeing's C-17 line wins a reprieve on new funding

- ↑ "Denmark Signs Up For Boeing C-17 In NATO Deal." Christie, R. The Wall Street Journal. July 19, 2006.

- ↑ Boeing Announces C-17 Line May End in mid-2009; Stops Procurement of Long-lead Parts

- ↑ "C-17/C-17 ER Flammable Material Locations." Boeing Integrated Defense Systems. May 1, 2005.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Fulghum, D., Butler, A., Barrie, D.: "Australia Picks C-17.", Aviation Week & Space Technology. March 13, 2006, page 43. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "avweek_20060313" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "avweek_20060313" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 9.0 9.1 O'Connell, Dominic. "Political clash haunts MoD deal decision", The Business, Sunday Business Group, 1999-12-05. Retrieved on 2007-02-07.

- ↑ "RAF's Globe Master." Global Defence Review. 2003.

- ↑ "MoD pins hopes on Boeing C17 amid Airbus doubts." Robertson, D. The Times. December 28, 2006.

- ↑ "Stock Standard." Aviation Week & Space Technology. December 11 2006.

- ↑ Defence to by C-17 Aircraft. Retrieved on 2006-05-09.

- ↑ "Boeing wins $780 mln deal for Australia C-17s." Reuters. Reuters. July 31, 2006.

- ↑ RAAF gets first of giant planes. Retrieved on 2006-11-29.

- ↑ First C-17 arrives in Australia. Retrieved on 2006-12-04.

- ↑ The Defence Review and General Rick Hillier.Canadian American Strategic Review 2005.

- ↑ "Stephen Harper announces the new defence policy put forward by the Conservative Party of Canada – Pt 7."Canadian American Strategic Review December 22,2005.

- ↑ "Canada First" Defence Procurement - New Strategic & Tactical Airlift Fleets Ministry of National Defence Press Release June 29, 2006

- ↑ Airlift Capability Project - Strategic ACP-S - ACAN MERX Website - Government of Canada

- ↑ Gov't Inks $3.4B Deal to Buy Boeing Jets: CTV. Retrieved on 2007-02-02.

- ↑ "Canada gets USAF slots for August delivery after signing for four Boeing C-17 in 20-year C$4bn deal, settles provincial workshare quabble." Wastnage, J. Flight International. February 5, 2007.

- ↑ NATO Stategic Airlift Capability

- ↑ NATO to place order for C-17s,Long Beach Press Telegram September 13,2006

- ↑ Strategic Airlift Capability

- ↑ NATO AWACS Homepage of the E-3 Component

- ↑ "Berlin designates tsunami relief as aid." Expatica. January 17, 2005.

- ↑ Background — Airlifters — NATO’s Strategic Airlift Interim Solution Canadian American Strategic Review (CASR) Simon Fraser University

- ↑ NATO Strategic Airlift Capability

- ↑ "Aussies learn C-17 ropes." Air Force Times. October 25, 2006.

- ↑ "Master plan for C-17s." Air Force News. Volume 48, No. 4, March 23, 2006

External links

- C-17 page on Boeing.com

- C-17 History page on Boeing.com

- C-17 USAF fact sheet

- C-17 detailed photographs

- C-17 web page on GlobalSecurity.org

- C-17 interior used for civilian transport

Related content

Related development

Comparable aircraft

Designation sequence

Related lists

- List of active United States military aircraft

- List of active United Kingdom military aircraft

- List of military aircraft of the United States

- List of military transport aircraft

- List of active Canadian military aircraft

See also

Fighters: XP-67 · FH · F2H · XF-85 · XF-88 · F3H · F-101 · F-110 · F-4 · F-15 · F/A-18 · CF-188 · YF-23 · F/A-18E/F

Attack: AH · AV-8 · F-15E · A-12 - Trainers: T-45

Transports: C-9 · KC-10 · YC-15 · C-17

Helicopters: XHJH · XH-20 · XHCH · XHRH · AH-64

Drones: TD2D · KDH - Experimental: XV-1 · X-36 · Bird of Prey - Spacecraft: Mercury · Gemini

Lists relating to aviation | |

|---|---|

| General | Timeline of aviation · Aircraft · Aircraft manufacturers · Aircraft engines · Aircraft engine manufacturers · Airports · Airlines |

| Military | Air forces · Aircraft weapons · Missiles · Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) · Experimental aircraft |

| Notable incidents and accidents | Military aviation · Airliners · General aviation · Famous aviation-related deaths |

| Records | Flight airspeed record · Flight distance record · Flight altitude record · Flight endurance record · Most produced aircraft |

de:McDonnell Douglas C-17 es:C-17 Globemaster III fr:McDonnell Douglas C-17 Globemaster III it:McDonnell Douglas C-17 Globemaster III ja:C-17 (輸送機) no:Boeing C-17 Globemaster III pl:McDonnell Douglas C-17 sl:McDonnell Douglas C-17 Globemaster III fi:C-17 Globemaster III sv:Boeing C-17 Globemaster III zh:C-17运输机