PlaneSpottingWorld welcomes all new members! Please gives your ideas at the Terminal.

P-51 Mustang

| P-51 Mustang | |

|---|---|

| North American P-51D Mustang Tika IV of the 361st Fighter Group, marked with D-day ("invasion") stripes | |

| Type | Fighter |

| Manufacturer | North American Aviation |

| Designed by | Edgar Schmued |

| Maiden flight | 26 October 1940 |

| Introduced | 1942 |

| Retired | 1957, US ANG |

| Primary users | United States Army Air Forces See Non-US service |

| Number built | 15,875 |

| Unit cost | US$50,985 in 1945[1] |

| Variants | A-36 Apache F-82 Twin Mustang Cavalier Mustang Piper PA-48 Enforcer Mustang X |

The North American P-51 Mustang was an American long-range single-seat fighter aircraft that entered service with Allied air forces in the middle years of World War II. The P-51 became one of the conflict's most successful and recognizable aircraft.

The P-51 flew most of its wartime missions as a bomber escort in raids over Germany, helping ensure Allied air superiority from early 1944. It also saw service against the Japanese in the Pacific War. The Mustang began the Korean War as the United Nations' main fighter but was supplanted as a fighter by jets early in the conflict, being relegated to a ground attack role. Nevertheless, it remained in service with some air forces until the early 1980s.

Despite being economical to produce, the Mustang was a well-made and rugged aircraft. The definitive version of the single-seat fighter was powered by the Packard V-1650-3, a two-stage two-speed supercharged 12-cylinder Packard-built version of the legendary Rolls-Royce Merlin engine, and armed with six aircraft versions of the .50 caliber (12.7 mm) Browning machine guns. Like most other fighters that used a liquid-cooled engine, its weakness was a coolant system that could be punctured by a single bullet.

After World War II and the Korean conflict, many Mustangs were converted for civilian use, especially air racing.

Contents

- 1 Genesis

- 2 Design and development

- 3 Allison-engined Mustangs

- 4 Merlin-engined Mustangs

- 5 The "lightweight" Mustangs

- 6 F-51 and RF-51

- 7 Production

- 8 Operational service

- 9 P-51 Pilot Medal of Honor Recipients

- 10 Non-US service

- 11 P-51s and civil aviation

- 12 Survivors

- 13 Scaled replicas

- 14 Specifications

- 15 P-51s in film

- 16 References

- 17 External links

- 18 Related content

Genesis

In 1939, shortly after World War II began, the British government established a purchasing commission in the United States, headed by Sir Henry Self. Along with Sir Wilfrid Freeman, who as the "Air Member for Development and Production" was given overall responsibility for RAF production and research and development in 1938, Self had sat on the (British) Air Council Sub-committee on Supply (or "Supply Committee"). One of Self's many tasks was to organize the manufacture of American fighter aircraft for the RAF. At the time, the choice was very limited. None of the US aircraft already flying met European standards; only the Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk came close. The Curtiss plant was running at capacity, so even that aircraft was in short supply.

North American Aviation (NAA) was already supplying their Harvard trainer to the RAF but were otherwise underutilized. NAA President Dutch Kindleberger approached Self to sell a new medium bomber, the B-25 Mitchell. Instead, Self asked if NAA could manufacture the Tomahawk under licence from Curtiss.

Kindleberger replied that NAA could have a better aircraft with the same engine in the air in less time than it would take to set up a production line for the P-40. As executive head of the British Ministry of Aircraft Production, Freeman ordered 320 aircraft in March 1940. On 26 June 1940, MAP awarded a contract to Packard to build modified versions of the Rolls-Royce Merlin engines under licence; in September, MAP increased the first production order by 300.

Design and development

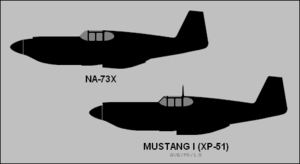

The result of the MAP order was the NA-73X project (from March 1940). The design followed the best conventional practice of the era, but included two new features. One was a new NACA-designed laminar flow wing, which was associated with very low drag at high speeds. Another was the use of a new radiator design that used the heated air exiting the radiator as a form of jet thrust in what is referred to as the "Meredith Effect." Because North American lacked a suitable wind tunnel, it was forced to use Curtiss's facility. This led to some controversy over whether the Mustang's aerodynamics were developed by North American's engineer Edgar Schmued or by Curtiss, although many authors dismiss the allegation of stolen technology.

The USAAC could block any sales it considered interesting, and this appeared to be the case for the NA-73. An arrangement was eventually reached where the RAF would get its planes, in exchange for NA providing two cost-free to the USAAC.

The prototype NA-73X was rolled out just 117 days after the order was placed, and first flew on 26 October 1940, just 178 days after the order had been placed - an incredibly short gestation period. In general, the prototype handled well and the internal arrangement allowed for an impressive fuel load. It was armed with four .50 M2 Browning (12.7 mm) guns and two .30 Browning (7.62 mm) guns. In comparison, the British Spitfire Vb carried two 20 mm cannon and four .303 machine guns.

Allison-engined Mustangs

Mustang I/P-51

It was quickly evident that performance, although exceptional up to 15,000 feet, was inadequate at higher altitudes. This deficiency was due largely to the mechanically supercharged Allison V-1710 engine, which lacked power at higher altitudes. Prior to the Mustang project, the USAAC had Allison concentrate primarily on turbochargers in concert with General Electric; these proved to be exceptional in the P-38 Lightning and other high-altitude aircraft. Most of the other uses for the Allison were for low-altitude designs, where a simple supercharger would suffice. The turbocharger proved impractical for fitting into the Mustang, and it was forced to use the inadequate superchargers available. Still, the Mustang's advanced aerodynamics showed to advantage, as the Mustang I was about 30 mph faster than contemporary Curtiss P-40 fighters using the same Allison powerplant. The Mustang I was 30 mph faster than the Spitfire Mk VC at 5,000 feet and 35 mph faster at 15,000 ft, despite the British plane's more powerful engine.[2]

The first production contract was awarded by the British for 320 NA-73 fighters named Mustang I by the British. Two aircraft of this lot delivered to the USAAF were designated XP-51. A second British contract called for 300 more (NA-83) Mustang I fighters. In September 1940, 150 aircraft designated NA-91 by North American were ordered under the Lend/Lease program. These were designated by the USAAF as P-51 and initially named the "Apache" although this designation was soon dropped and the RAF name, "Mustang," adopted instead. The British designated this model as Mustang IA. They were equipped with four long-barrelled 20 mm Hispano-Suiza Mk II cannon instead of machine guns.

A number of aircraft from this lot were fitted out by the USAAF as photo reconnaissance aircraft and designated F-6A. The British would fit a number of Mustang Is with similar equipment. Also, two aircraft of this lot were fitted with the Packard built Merlin engine and were designated by North American as model NA-101 and by the USAAF initially as the XP-78, but re-designated to XP-51B.

About 20 of the Mustang Mk I were delivered to the RAF and made their combat debut on 10 May 1942. With their long range and excellent low-level performance, they were employed effectively for tactical reconnaissance and ground-attack duties over the English Channel, but were thought to be of limited value as fighters due to their poor performance above 15,000 feet.

The Mustang Mk IA was identical to the Mustang Mk I except that the machine guns were removed and replaced with four wing mounted 20 mm cannons.

A-36 Apache/Invader

At the same time, the USAAC was becoming more interested in ground attack planes and had a new version ordered as the A-36 Apache, which included six .50 M2 Browning machine guns, dive brakes and the ability to carry two 500 pound (230 kg) bombs.

In early 1942, the USAAF ordered 500 aircraft modified as dive bombers that were designated A-36A (NA-97). This model became the first USAAF Mustang to see combat. One aircraft was passed to the British who gave it the name Mustang I (Dive Bomber).

Merlin-engined Mustangs

P-51B and P-51C

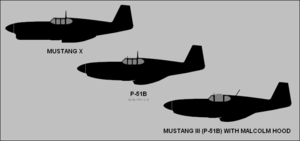

In April 1942, the RAF's Air Fighter Development Unit (AFDU) tested the Mustang at higher altitudes and found its performance inadequate, but the commanding officer was so impressed with its maneuverability and low-altitude speeds that he invited Ronnie Harker from Rolls Royce's Flight Test establishment to fly it. Rolls-Royce engineers rapidly realized that equipping the Mustang with a Merlin 61 would substantially improve performance and started converting five aircraft as the Mustang X. Ministry official Sir W.R. Freeman lobbied vociferously for Merlin-powered Mustangs, insisting two of the five experimental Mustang Xs be handed over to Carl Spaatz for trials and evaluation by the US 8th Air Force in Britain.[3]

The high-altitude performance improvement was astonishing: the Mustang X AM208 reached 433 mph at 22,000 ft and AL975 tested at an absolute ceiling of 40,600 ft.[4]After sustained lobbying at the highest level, American production of a North American-designed Mustang, with the Packard Merlin V-1650 engine replacing the Allison, was started in early 1943. The pairing of the P-51 airframe and Merlin engine was designated P-51B or P-51C (B (NA-102) being manufactured at Inglewood, California, and C (NA-103) at a new plant in Dallas, Texas, in operation by summer 1943). The RAF named these models Mustang III. In performance tests, the P-51B reached 441 mph/709.7 km/h at 25,000 ft (7.600 m) and the subsequent extended range made possible by the use of drop tanks enabled the Merlin-powered Mustang to be introduced as a bomber escort.

P-51Bs and Cs started to arrive in England in August and October 1943. The P-51B/C versions were sent to 15 fighter groups that were part of the 8th and 9th Air Forces in England, and the 12th and 15th in Italy (the southern part of Italy was under Allied control by late 1943). Other deployments included the China Burma India Theater (CBI).

Allied strategists quickly exploited the long-range fighter as a bomber escort. It was largely due to the P-51 that daylight bombing raids deep into German territory became possible without prohibitive bomber losses in late 1943.

A number of the P-51B and P-51C aircraft were fitted for photo reconnaissance and designated F-6C.

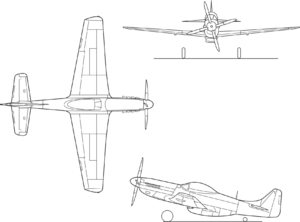

P-51D and P-51K

One of the few remaining complaints with the Merlin-powered aircraft was a poor rearward view. This was a common problem in most fighter designs of the era, which had only been recognized by the British after the Battle of Britain proved the value of an all-around view. In order to improve the view from the Mustang at least partially, the British had field-modified some Mustangs with fishbowl-shaped canopies called "Malcolm Hoods." Eventually all Mk IIIs, along with some American P-51B/Cs, were equipped with Malcolm Hoods.

A better solution to the problem was the "bubble" canopy. Originally developed as part of the Miles M.20 project, these newer canopies were in the process of being adapted to most British designs, eventually appearing on late-model Spitfires, Typhoons and Tempests. North American adapted several NA-106 prototypes with a bubble canopy, cutting away the decking behind the cockpit to allow looking directly to the rear. This led to the production P-51D (NA-109), considered the definitive Mustang.

A common misconception is that cutting down the rear fuselage to mount the bubble canopy reduced stability, requiring the addition of a dorsal fin to the forward base of the vertical tail. Actually, both the B/C and later D/K models had a low speed handling problem that could result in an involuntary "snap-roll" under certain conditions of air speed, angle of attack, gross weight and center of gravity. Several crash reports tell of P-51Bs and Cs crashing because horizontal stabilizers were torn off during maneuvering. One report stated:

- "Unless a dorsal fin is installed on the P-51B, P-51C and P-51D airplanes, a snap roll may result when attempting a slow roll. The horizontal stabilizer will not withstand the effects of a snap roll. To prevent recurrence the stabilizer should be reinforced in accordance with T.O. 01-60J-18 dated 8 April 1944 and a dorsal fin should be installed. Dorsal fin kits are being made available to overseas activities"

While some existing aircraft do not have the dorsal extension fitted, many were equipped at some point in their service or refurbishment with a taller tail, which provided a similar increase in yaw stability. Also, civilian-owned examples often have newer, lighter radios, an absence of external munitions and drop tanks, removed guns and armor plate and an empty or removed fuselage tank - reducing the need for the dorsal fin.

Among other modifications, armament was increased with the addition of another two M2 machine guns, bringing the total to six. The inner pair of machine guns had 400 rounds each, and the others had 270 rounds, for a total of 1,880. In previous P-51s, the M2s were mounted at angles that led to frequent complaints of jamming during combat maneuvers. The new arrangement allowed the M2s to be mounted in a more standard manner that remedied most of the jamming problems. The .50 caliber Browning machine guns, although not firing an explosive projectile, had excellent ballistics and proved adequate against the Fw 190 and Bf 109 fighters that were the main USAAF opponents at the time. Later models had under-wing rocket pylons added to carry up to ten rockets per plane.

The P-51D became the most widely produced variant of the Mustang. A Dallas-built version of the P-51D, designated the P-51K, was equipped with an Aeroproducts propeller in place of the Hamilton Standard propeller, as well as a larger, differently configured canopy and other minor alterations (the vent panel was different). The hollow-bladed Aeroproducts propeller was unreliable with dangerous vibrations at full throttle due to manufacturing problems and was eventually replaced by the Hamilton Standard. The photo versions of the P-51D and P-51K were designated F-6D and F-6K respectively. The RAF assigned the name Mustang IV to the D model and Mustang IVA to K models.

The P-51D/K started arriving in Europe in mid-1944 and quickly became the primary USAAF fighter in the theater. It was produced in larger numbers than any other Mustang variant. Nevertheless, by the end of the war, roughly half of all operational Mustangs were still B or C models.

From 1945-1948, P-51Ds were also built under licence in Australia by the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation (see below).

The "lightweight" Mustangs

XP-51F, XP-51G and XP-51J

The USAAF required airframes built to their acceleration standard of 8.33 g (82 m/s²), a higher load factor than that used by the British standard of 5.33 g (52 m/s²) for their fighters. Reducing the load factor to 5.33 would allow weight to be removed, and both the USAAF and the RAF were interested in the potential performance boost.

In 1943, North American submitted a proposal to re-design the P-51D as model NA-105, which was accepted by the USAAF. Modifications included changes to the cowling, a simplified undercarriage with smaller wheels and disk brakes, and a larger canopy. The designation XP-51F was assigned to prototypes powered with V-1650 engines (a small number of XP-51Fs were passed to the British as the Mustang V) and XP-51G to those with reverse lend/lease Merlin 145M engines.

A third lightweight prototype powered by an Allison V-1710-119 engine was added to the development program. This aircraft was designated XP-51J. Since the engine was insufficiently developed, the XP-51J was loaned to Allison for engine development. None of these experimental "lightweights" went into production.

P-51H

The P-51H (NA-126) was the final production Mustang, embodying the experience gained in the development of the XP-51F and XP-51G aircraft. This aircraft, with minor differences as the NA-129, came too late to participate in World War II, but it brought the development of the Mustang to a peak as one of the fastest production piston engine fighters to see service.

The P-51H used the new V-1650-9 engine, a version of the Merlin that included Simmons automatic supercharger boost control with water injection, allowing War Emergency Power as high as 2218 hp (1,500 kW). Differences between the P-51D included lengthening the fuselage and increasing the height of the tailfin, which greatly reduced the tendency to yaw. The canopy resembled the P-51D style, over a somewhat raised pilot's position. Service access to the guns and ammunition was also improved. With the new airframe several hundred pounds lighter, the extra power and a more streamlined radiator, the P-51H was among the fastest propeller fighters ever, able to reach 487 mph (784 km/h) at 25,000 ft (7,600 m).

The P-51H was designed to complement the P-47N Thunderbolt as the primary aircraft for the invasion of Japan with 2,000 ordered to be manufactured at Inglewood. Production was just ramping up with 555 delivered when the war ended. Production serial numbers:

- P51H-1-NA 44-64160 - 44-64179

- P51H-5-NA 44-64180 - 44-64459

- P51H-10-NA 44-64460 - 44-64714

Additional orders, already on the books, were cancelled. With the cutback in production, the variants of the P-51H with different versions of the Merlin engine were produced in either limited numbers or terminated. These included the P-51L, similar to the P-51H but utilizing the 2270 horsepower V-1650-11 Merlin engine, which was never built; and its Dallas-built version, the P-51M or NA-124 which utilized the V-1650-9A Merlin engine lacking water injection and therefore rated for lower maximum power, of which one was built out of the original 1629 ordered, serial number 45-11743.

Although some P-51Hs were issued to operational units, none saw combat in World War II, and in postwar service, most were issued to reserve units. One aircraft was provided to the RAF for testing and evaluation. Serial number 44-64192 was designated BuNo 09064 and used by the US Navy to test transonic airfoil designs, then returned to the Air National Guard in 1952. The P-51H was not used for combat in the Korean War despite its improved handling characteristics, since the P-51D was available in much larger numbers and was a proven commodity.

Many of the aerodynamic advances of the P-51 (including the laminar flow wing) were carried over to North American's jet-powered next generation of fighters, the Navy FJ Fury and Air Force F-86 Sabre. The wings, empennage and canopy of the straight-winged first variant of the Fury (the FJ-1) and the unbuilt preliminary prototypes of the P-86/F-86 strongly resembled those of the Mustang before the aircraft were modified with swept-wing design.

F-51 and RF-51

In 1948, the designation P-51 (P for pursuit) was changed to F-51 (F for fighter) and the existing F designator for photographic reconnaissance aircraft was dropped because of a new designation scheme throughout the USAF. During the Korean War, F-51s, though obsolete as fighters, were used as tactical bombers and reconnaissance aircraft. Because of its lighter structure and less availability of spare parts, the newer, faster F-51H was not used in Korea. With the planes being used for ground attack, their performance was less of a concern than their ability to carry a load. Aircraft still in service in the USAF or Air National Guard (ANG) when the system was changed included: F-51B, F-51D, F-51K, RF-51D (formerly F-6D), RF-51K (formerly F-6K), and TRF-51D (two-seat trainer conversions of F-6Ds).

The F-51 was adopted by many air forces, the Israeli Air Force using them in the War of Independence (1948) and in Operation Kadesh (1956). The last Mustangs were retired from USAF/Air National Guard service in 1957 but remained in use as test beds/chase aircraft into the 1960s and later. Many remain airworthy across the globe, in private hands. A few of those have been modified for extra speed for competing in air racing.

Production

- P-51A: 310 built at Inglewood, California

- P-51B: 650 built at Inglewood

- P-51C: 3,750 built at Dallas, Texas

- P-51D/K: 6,502 built at Inglewood; 1,454 at Dallas; 200 by CAC at Fisherman's Bend, Australia. A total of 8,156.

- P-51H: 555 built at Inglewood

- P-51M: one built at Dallas

Total number built: 15,875 (among American fighter aircraft second only to the P-47 Thunderbolt)

Operational service

At the Casablanca Conference, the Allies formulated the Combined Bomber Offensive (CBO) plan for "round-the-clock" bombing by the RAF at night and the USAAF by day. American pre-war bombardment doctrine held that large formations of heavy bombers flying at high altitudes would be able to defend themselves against enemy interceptors with minimal fighter escort, so that precision daylight bombing using the Norden bombsight would be effective.

Both the RAF and Luftwaffe had attempted daylight bombing and discontinued it, believing advancements in single-engine fighters made multi-engined bombers too vulnerable, contrary to Douhet's thesis. The RAF had worried about this in the mid-1930s and had decided to produce an all night-bomber force, but initially began bombing operations by day. The Germans used extensive daylight bombing during the Battle of Britain in preparation for a possible invasion. The Luftwaffe found daylight bombing raids sustained high casualties and soon switched to night bombing (see The Blitz). Bomber Command followed suit in its subsequent raids over Germany.

Initial USAAF efforts were inconclusive because of the limited scale. In June 1943, the Combined Chiefs of Staff issued the Pointblank Directive to destroy the Luftwaffe before the invasion of Europe, putting the CBO into full implementation. The Eighth Air Force heavy bomber force conducted a series of deep penetration raids into Germany beyond the range of available escort fighters. German fighter reaction was fierce and bomber losses were severe — 20 percent in an October 14 attack on the German ball-bearing industry. This made it impossible to continue such long-range raids without adequate fighter escort.

The Lockheed P-38 Lightning had the range to escort the bombers, but was available in very limited numbers in the European theater due to its degraded performance at frigid high altitudes and its Allison engines proving difficult to maintain. With the extensive use of the P-38 in the Pacific war, where its twin engines were deemed vital to long-range "over-water" operations, nearly all European-based P-38 units converted to the P-51 in 1944. The Republic P-47 Thunderbolt was capable of meeting the Luftwaffe on even terms, but did not then have sufficient range. The Mustang changed all that. In general terms, the Mustang was at least as simple as other aircraft of its era. It used a single, well-understood, reliable engine, and had internal space for a huge fuel load. With external fuel tanks, it could accompany the bombers all the way to Germany and back.

Enough P-51s became available to the 8th and 9th Air Forces in the winter of 1943-44, and when the Pointblank offensive resumed in early 1944, matters changed dramatically. The P-51 proved perfect for the task. The Eighth Air Force immediately began to switch its fighter groups to the Mustang, first exchanging arriving P-47 groups for those of the Ninth Air Force using P-51s, then gradually converted its Thunderbolt and Lightning groups until eventually 14 of its 15 groups flew the Mustang.

Luftwaffe pilots attempted to avoid US fighters by massing in huge numbers well in front of the bombers, attacking in a single pass, then breaking off the attack, allowing escorting fighters little time to react. While not always successful in avoiding contact with escort (as the tremendous loss of German pilots in the spring of 1944 indicates), the threat of mass attacks, and later the "company front" (eight abreast) assaults by armored sturmgruppe Fw 190s, brought an urgency to attacking the Luftwaffe wherever it could be found. The P-51, particularly with the advent of the K-14 gunsight and the development of "Clobber Colleges" for the in-theater training of fighter pilots in the fall of 1944, was a decisive element in Allied countermeasures against the Jagdverbände.

In May 1944, the fighters of Allied Tactical Air Forces were granted permission to "free-hunt",[citation needed] roaming away from the bombers after providing fighter cover and attacking German planes at Luftwaffe airfields. The numerical superiority of the USAAF fighters, superb flying characteristics of the P-51 and pilot proficiency crippled the Luftwaffe. As a result, the fighter threat to US, and later British bombers, was greatly diminished by the summer of 1944.

USAAF Tactical Air Forces then concentrated on ground targets, trains, military equipment, etc., in preparation for and in support of the Allied invasion of France.

P-51s also distinguished themselves against advanced enemy rockets and aircraft. A P-51B/C with high-octane fuel was fast enough to pursue the V-1s launched toward London. The Me 163 Komet rocket interceptors and Me 262 jet fighters were considerably faster than the P-51, but not invulnerable. Chuck Yeager, flying a P-51D, was one of the first American pilots to shoot down a Me 262 when he surprised it during its landing approach.

The Eighth, Ninth and Fifteenth Air Forces' P-51 groups, all but three of which flew another type before converting to the Mustang, claimed some 4,950 aircraft shot down (about half of all USAAF claims in the European theater) and 4,131 destroyed on the ground. Losses were about 840 aircraft. One of these groups, the Eighth Air Force's 4th Fighter Group, was the overall top-scoring fighter group in Europe with 1,016 enemy aircraft destroyed, 550 in aerial combat and 466 on the ground [3]. In aerial combat, the top-scoring P-51 units (both of which exclusively flew Mustangs) were the 357th Fighter Group of the Eighth Air Force with 595 air-to-air combat victories, and the Ninth Air Force's 354th Fighter Group with 701, which made it the top scoring outfit in aerial combat of all fighter groups of any type. Martin Bowman reports that in the ETO Mustangs flew 213,873 sorties and lost 2,520 aircraft to all causes.

P-51s were deployed in the Far East later in 1944, operating in both close-support and escort missions.

Post-World War II

In the aftermath of World War II, the USAAF consolidated much of its wartime combat force and selected the P-51 as a "standard" piston engine fighter while other types such as the P-38 and P-47 were withdrawn or given substantially reduced roles. However, as more advanced jet fighters (P-80 and P-84) were being introduced, the P-51 was relegated to secondary status. In 1947, the newly-formed USAF Strategic Air Command employed Mustangs (redesignated the F-51) alongside F-6 Mustangs and F-82 Twin Mustangs, due to their range capabilities. They remained in service from 1946 through 1951. By 1950, although Mustangs continued in service with the USAF and many other nations after the war, the majority of the USAF's Mustangs had been surplussed or transferred to the Reserve and the Air National Guard (ANG).

At the start of the Korean War, the Mustang once again proved its usefulness. With the availability of F-51Ds in service and in storage, a substantial number were shipped via aircraft carriers to the combat zone for use initially by both the Republic of Korea Air Force (ROKAF) and USAF. Rather than employing them as interceptors or "pure" fighters, the F-51 was given the task of ground attack, fitted with rockets and bombs. After the initial invasion from North Korea, USAF units were forced to fly from bases in Japan, and F-51Ds could hit targets in Korea that short-ranged F-80 jet fighters could not. A major concern over the vulnerability of the cooling system was realized in heavy losses due to ground fire. Mustangs continued flying with USAF, Republic of Korea Air Force (ROKAF), South African Air Force (SAAF) and Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) fighter-bomber units on close support and interdiction missions in Korea until they were largely replaced by Republic F-84 and Grumman Panther jet fighter-bombers in 1953. The South Africans continued to fly their 95 Mustangs in Korea but lost many of them by 1952.

F-51s flew in the USAF Reserve and ANG until they were finally phased out in 1957.

P-51 Pilot Medal of Honor Recipients

Three US fighter pilots were awarded the Medal of Honor for actions while flying the P-51.

Former "Flying Tiger" Major James H. Howard of the 354th Fighter Group was awarded the Medal of Honor for action over Germany on 11 January 1944 while flying a P-51B, when he was separated from the rest of his flight while escorting a formation of B-17 bombers which then came under attack from over 30 German fighters which he then took on singlehandedly. While Howard only claimed two kills, crewmen on the B-17s reported that he downed at least six German fighters.

Major William A. Shomo, commander of the 82nd Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron, was awarded the Medal of Honor for action over the Philippines on 11 January 1945, a year to the day after Howard's action. Flying F-6Ds on an armed recon mission, Shomo and his wingman spotted and attacked a flight of 12 Japanese fighters escorting a Betty bomber. Shomo downed the bomber and six of the escorting fighters while his wingman downed three more of the escorts.

Major Louis J. Sebille of the 67th Fighter Squadron was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for action over Korea on 5 August 1950. Flying on a ground attack mission against a heavy troop concentration, his F-51D sustained severe damage from enemy ground fire. Rather than attempting to return to base or bail out over friendly territory, he continued his attacks until finally deliberately diving his Mustang into an enemy antiaircraft battery.

Non-US service

The P-51 Mustang remained in service with more than 30 air forces after World War II; the last was retired from active service in the early 1980s. Here is a list of some of the countries that used the P-51 Mustang.

- Argentina

- Australia

The first Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) unit to use Mustangs was No. 3 Squadron RAAF, which converted to them at its base in Italy in November 1944. The RAAF had also decided to replace its P-40 Kittyhawks in the South West Pacific Area with P-51s, and ordered a total of about 500 Mustangs, which were to be built by the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation (CAC), the only non-US production line. In 1944, 100 P-51Ds were shipped from the US in kit form to inaugurate production at Fishermans Bend, in Melbourne. CAC assembled 80 of these under the designation CA-17/Mark 20, the remaining 20 being kept unassembled as part spares.

CAC then produced on its own 120 more P-51Ds (reduced from an initial order for 170), which it designated CA-18/Mark 21, 22, or 23. (The RAAF used the serial number prefix A68 for all P-51s.). Mk 22 was a photo reconnaissance variant and Mk 23 had newer model British-made Merlin engines. In addition, 84 P-51Ks were also shipped direct to the RAAF from the USA. However, only 17 Mustangs reached the frontline squadrons of the First Tactical Air Force by the time World War II ended in August 1945. The RAAF cancelled orders for about 200 Mustangs. No. 77 Squadron RAAF also used P-51s extensively during the first years of the Korean War, before converting to Gloster Meteor jets.

- Bolivia

Nine Cavalier F-51D (including the two TF-51s) were given to Bolivia, under a program called Peace Condor.

- Canada

Canada had five squadrons equipped with Mustangs during World War II. RCAF No. 400, 414 and 430 squadrons flew Mustang Mk 1s (1942-1944) and nos. 441 and 442 flew Mustang Mk IIIs and IVAs in 1945. Postwar, a total of 150 Mustang P-51Ds were purchased and served in two regular: no. 416 "Lynx" and no. 417 "City of Windsor" and six auxiliary fighter squadrons: no. 402 "City of Winnipeg," no. 403 "City of Calgary," no. 420 "City of London," no. 424 "City of Hamilton," no. 442 "City of Vancouver" and no. 443 "City of New Westminister." The Mustangs were declared obsolete in 1956; a number of special-duty versions served on into the early 1960s.

- China (People's Republic)

Several hundred P-51s were given to the Allied Air Forces in China. They were also used by the Chinese Communists until the late 1950s.

- Costa Rica

The Costa Rica Air Force flew four F-51s from 1955-1964.

- Cuba

Some reports claim that under the terms of the Rio Pact of 1947, Cuba was supplied with F-51D Mustangs. These reports appear to be erroneous. However, after when Fidel Castro seized control of Cuba in 1959, Cuba's Fuerza Aerea Revolucionaria illegally acquired three ex-civilian Mustangs reputedly being bought in Canada by envoys of Fidel Castro. The P-51 Mustangs did not enter service soon enough to see any action during the Cuban revolution. During the Bay of Pigs Invasion, the Mustangs were damaged on the ground, and were repaired too late to participate in the fighting. They served with the Cuban air force until they were replaced with Russian-built equipment in the early 1960s.[5]

- Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic (FAD) largest Latin American air force to employ the F-51D with 44 acquired in 1948. It was the The last nation to have the F-51 Mustang in service, with some remaining in use as late as 1984.

- El Salvador

The three Cavalier Mustang IIs (F-51K) built for El Salvador featured wingtip fuel tanks to increase combat range. Seven F-51D Mustangs were also in service.

- France

In late 1944, the first French unit began its transition to reconnaissance Mustangs. In January 1945, the Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron 2/33 of the French Air Force took their F-6Cs and F-6Ds over Germany on photographic mapping missions. The Mustangs remained in service until the early 1950s when they were replaced by jet fighters.

- Guatemala

Guatemala (FAG) had 30 P-51s in service from 1954 to the early 1970s.

- Haiti

Haiti had two Mustangs when President Paul Eugène Magloire was in power between 1950 and 1956.

- Honduras

Seven Mustangs were acquired from private sources to fight in the so-called "Football War."

- Indonesia

Indonesia acquired some F-51s from the departing Netherlands East Indies Air Force in 1949/1950. The Mustangs were used against Commonwealth (RAF, RAAF and RNZAF) forces during the Indonesian confrontation in the early 1960s. The last time Mustangs were to be deployed for military purposes was a shipment of six Cavalier II Mustangs (without tip tanks)[4] [5] delivered to Indonesia in 1972-1973, which were replaced in 1976.

- Israel

A few P-51 Mustangs were illegally bought by Israel in 1948 and quickly established themselves as the best fighter in the Israeli inventory. Further aircraft were bought from Sweden and Nicaragua but were replaced by jets at the end of the 1950s, but not before the type was used in the Suez Crisis.

- Italy

After Italy quit the Axis and switched over to the Allies, the Italian air force was supplied with American equipment, including P-51Ds. By late 1948, Italy had 48 Mustangs in service, remaining as front-line equipment until replaced by Vampires and Sabres in 1953.

- Japan

The P-51C-11-NT "Evalina" marked as "278" (former USAAC serial:44-10816) flown by 26th FS, 51st FG, was hit by gunfire on 16 January 1945 and belly landed on Suchon Airfield in China which was held by the Japanese. The Japanese repaired the aircraft, roughly applied Hinomarus and flew the aircraft to the Fussa evaluation centre (now Yokota Air Base) in Japan.

- Netherlands

The Netherlands East Indies Air Force received 40 P-51s and flew them in the Indonesian conflict. When the conflict was over Indonesia received some of the NEIAF mustangs.

- Nicaragua

Nicaragua (GN) gained 26 Mustangs from Sweden in 1954 and used them until 1964.

- New Zealand

New Zealand ordered 320 P-51 Mustangs as a partial replacement of its F4U Corsairs in the Pacific Ocean Areas theatre. Thirty were delivered in 1945 but the war ended before they entered service. The remainder were retained in the US. The 30 received were placed in storage (left in their packing cases) until 1950 when put into service with the New Zealand Territorial Air Force (TAF)'s Auckland, Wellington, Canterbury and Otago squadrons. The TAF was disbanded in 1957 and the Mustangs retired, one being retained by 42 Squadron for regular target towing duties, the remainder were sold for scrap. RNZAF pilots in the Royal Air Force also flew the P-51 and at least one New Zealand pilot scored victories over Europe while on loan to a USAAF P-51 squadron. A Mustang is on display in the RNZAF Museum and three other privately owned Mustangs are airworthy in the country.

- Philippines

After World War II, the Philippines were issued with P-51 Mustangs. These were to become the backbone of the Philippines Air Force and were extensively used during the Huk campaign, fighting against communist insurgents. They were replaced by F-86 Sabre jets in the late 1950s.

- Poland

During World War II, Polish Air Force in Great Britain squadrons used Mustangs. The first Polish unit equipped (7 June 1942) with Mustang Mk Is was Flight B of No. 309 Polish Army-Cooperation Squadron, followed by Flight A in March 1943. Subsequently, 309 Squadron was renamed No. 309 Polish Fighter-Reconnaissance Squadron and became part of Fighter Command. On 13 March 1944, No. 316 Polish Fighter Squadron received their first Mustang Mk IIIs; rearming of the unit was completed by the end of April. By 26 March 1943, No. 306 Polish Fighter Squadron and No. 315 Polish Fighter Squadron received Mustangs Mk IIIs (the whole operation took 12 days). On 20 October 1944, Mustang Mk Is in No. 309 Squadron were replaced by Mk IIIs. On 11 December 1944, the unit was again renamed, as No. 309 Polish Fighter Squadron. In 1945, No. 303 Polish Fighter Squadron received 20 Mustangs Mk IV/Mk IVA replacements. Postwar, between 6 December 1946 and 6 January 1947, all five Polish squadrons equipped with Mustangs were disbanded. Poland returned approximately 80 Mustangs Mk IIIs and 20 Mustangs Mk IV/IVAs to the RAF, which transferred them to the US government.[6]

- Somalia

- South Africa

The South African Air Force operated a number of Mustang Is and IIs (P-51As) in Italy and the Middle East during World War II. After VE-Day, these machines were soon struck off charge and scrapped. In 1950, 2 Squadron SAAF was supplied with F-51D Mustangs by the United States for Korean War service. The type performed well in South African hands before being replaced by the F-86 Sabre in 1952/1953.

- South Korea

Within a month of the outbreak of the Korean War, 10 F-51D Mustangs were provided to the badly depleted Republic of Korea Air Force as a part of the Bout One Project. They were flown by both South Korean airmen, several of whom were veterans of the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy air services during World War II as well as by US advisors led by Major Dean Hess. Later, more were provided both from US and from South African stocks, as the latter were converting to F-86 Sabres. They formed the backbone of the South Korean Air Force until they were replaced by Sabres.

- Soviet Union

The Soviet Union received at least 10 early-model Mustangs and tested them in combat. Some reports suggest that other Mustangs that were abandoned in Russia after the famous "shuttle missions" were repaired and used by the Soviet Air Force, but not in front-line service.

- Sri Lanka

- Sweden

Sweden's Flygvapnet first recuperated a handful of P-51s that had been diverted to Sweden during missions over Europe. In February 1945, Sweden purchased 50 P-51Ds designated J 26, which were delivered by American pilots in April and assigned to the F 16 wing at Uppsala as interceptors. In early 1946, the F 4 wing at Östersund was equipped with a second batch of 90 P-51Ds. A final batch of 21 airplanes was purchased in 1948. In all, 161 J 26s served in the Swedish Air Force during the late 1940s. About a dozen were modified for photo reconnaissance and re-designated S 26. (A few of these planes participated in the top secret Swedish mapping of new Soviet military installations at the Baltic coast in 1946-47, a project that entailed many intentional violations of Soviet airspace. However, the Mustang could outdive any Soviet fighter of that era, so no S 26 was lost in these missions.) The J 26s were replaced by De Havilland Vampires around 1950. The S 26s were replaced by S 29Cs in the early 1950s.

- Switzerland

Switzerland operated a few USAAF P-51s which had been impounded by the Swiss authorities during World War II after the pilots were forced to land in neutral Switzerland. They also bought 130 P-51s for $4,000 each. They served till 1958.

- Taiwan (Nationalist China)

Some of the P-51s given to China after World War II ended up in Taiwan when their pilots sided with Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist government. Further P-51s were acquired from the USAF and other sources. Many P-51s were subesquently lost to the Communist People's Liberation Army Air Force during the Nationalist retreat from the Chinese mainland.

- United Kingdom

The RAF was the first air force to operate the P-51 which was originally designed to meet RAF requirements. The first P-51As (RAF Mustang Is) entered service in 1941, wearing the standard RAF fighter markings. Due to poor high altitude performance, the Mustangs were soon transferred to Army co-operation and fighter reconnaissance duties, and were used extensively to seek out V-1 sites during 1943/1944. The final RAF Mustang I and Mustang II machines were struck off charge in 1945. The RAF operated several Mustang III (P-51B/C) machines, the first units converting to the type in late 1943/1944. Mustang III units were operational until the end of World War II, though many units had already converted to the Mustang IV (P-51D/K). RAF pilots preferred the Mustang III (with Malcolm hood), but the RAF re-equipped with Mustang IVs. As the Mustang was a Lend-Lease type, all aircraft still on RAF charge at the end of the war were either returned to the USAAF "on paper" or retained by the RAF for scrapping. The final Mustangs were retired from RAF use in 1947.

- Uruguay

Uruguay (FAU) used 25 F-51D Mustangs from 1950 to 1960 - some were subsequently sold to Bolivia.

- Venezuela

Venezuela (FAV) used only a sole Mustang which was acquired from another Latin American country.

P-51s and civil aviation

Many P-51s were sold as surplus after the war, often for as little as $1,500. Some were sold to former wartime fliers or other aficionados for personal use, while others were modified for air racing.[6]

One of the most prominent Mustangs involved in air racing was a surplus P-51C purchased by Paul Mantz, a film stunt pilot. The plane was modified by creating a "wet wing", sealing the wing to create a giant fuel tank in each wing, which eliminated the need for fuel stops or drag inducing drop tanks. This Mustang, called "Blaze of Noon," came in first in the 1946 and 1947 Bendix Air Races, second in the 1948 Bendix and third in the 1949 Bendix. He also set a US coast-to-coast record in 1947. This Mustang was sold to Charles Blair (future husband of Maureen O'Hara) and re-named "Excaliber III." Blair used it to set a New York-to-London record in 1951. Later that same year he flew from Norway to Fairbanks, Alaska, via the North Pole, proving that navigation via sun sights was possible over the magnetic north pole region. For this feat, he was awarded the Harmon Tropy and the Air Force was forced to change its thoughts on a possible Soviet air strike from the north. This Mustang now resides in the National Air and Space Museum at Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center.

The most prominent firm to convert Mustangs to civilan use was Trans-Florida Aviation, later renamed Cavalier Aircraft Corporation, which produced the Cavalier Mustang. Modifications included a taller tailfin and wingtip tanks. A number of conversions included a Cavalier Mustang specialty: a "tight" second seat added in the space formerly occupied by the military radio and fuselage fuel tank.

Ironically, in the late 1960s and early 1970s when the United States Department of Defense wished to supply aircraft to South American countries and later Indonesia, for close air support and counter insurgency, it turned to Cavalier to return some of their civilian conversions back to updated military specifications.

The P-51 is perhaps the most sought after of all warbirds on the civilian market; the average price usually exceeds $1 million USD, even for only partially restored aircraft.[7] Some privately owned P-51s are still flying, often associated with organizations such as the Commemorative Air Force (formerly the Confederate Air Force); [8]

Survivors

Among the 287 current airframes and the 154 "flying" Mustangs is:[7]

- P-51D "Mustang" Olympic flight museum, Olympia, Wa. In flying condition.

- P-51 "Mustang" Mrk IV Vintage Wings of Canada, Gatineau, Québec.

Scaled replicas

The P-51 has been the subject of numerous sub-scale flying replicas; aside from ever-popular R/C-controlled aircraft, several kitplane manufacturers offer 3/4-scale replicas capable of comfortably seating one (or even two) pilot(s) and offering high-performance combined with more forgiving flight characteristics. Such aircraft include the Titan T-51 Mustang and Thunder Mustang.

Specifications

P-51D Mustang

Data from The Great Book of Fighters,[8] and Quest for Performance[9]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 32 ft 3 in (9.83 m)

- Wingspan: 37 ft 0 in (11.28 m)

- Height: 13 ft 8 in (4.17 m)

- Wing area: 235 ft² (21.83 m²)

- Empty weight: 7,635 lb (3,465 kg)

- Loaded weight: 9,200 lb (4,175 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 12,100 lb (5,490 kg)

- Powerplant: 1× Packard Merlin V-1650-7 liquid-cooled supercharged V-12, 1,695 hp (1,265 kW)

- Zero-lift drag coefficient: 0.0163

- Maximum speed: 437 mph (703 km/h) at 25,000 ft (7,620 m)

- Cruise speed: 362 mph (580 km/h)

- Stall speed: 100 mph (160 km/h)

- Range: 1,650 mi (2,655 km) with external tanks

- Service ceiling: 41,900 ft (12,770 m)

- Rate of climb: 3,200 ft/min (16.3 m/s)

- Wing loading: 39 lb/ft² (192 kg/m²)

- Power/mass: 0.18 hp/lb (300 W/kg)

- 6x 0.50 in (12.7 mm) machine guns; 400 rounds per gun for the two inboard guns; 270 per outboard gun

- 2 hardpoints for up to 2,000 lb (907 kg)

- 10x 5 in (127 mm) rockets

P-51H Mustang

Data from The Great Book of Fighters[8]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 33 ft 4 in (10.16 m)

- Wingspan: 37 ft 0 in (11.28 m)

- Height: 11 ft 1 in (3.38 m)

- Wing area: 235 ft² (21.83 m²)

- Empty weight: 7,040 lb (3,195 kg)

- Loaded weight: 9,500 lb (4,310 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 11,500 lb (5,215 kg)

- Powerplant: 1× Packard Merlin V-1650-9 liquid-cooled supercharged V-12, 1,380 hp (1,030 kW) military, 2,218 hp (1,655 kW) WEP

Performance

- Maximum speed: 487 mph (784 km/h) at 25,000 ft (7,620 m)

- Range: 1,160 mi (1,865 km) with external tanks

- Service ceiling: 41,600 ft (12,680 m)

- Rate of climb: 3,300 ft/min (16.8 m/s)

- Wing loading: 40.4 lb/ft² (197.4 kg/m²)

- Power/mass: 0.23 hp/lb (385 W/kg)

- 6x 0.50 in (12.7 mm) Browning machine guns with 1,880 total rounds (400 rounds for each on the inner pair, and 270 rounds for each of the outer two pair), or 4 of the same guns with 1,600 total rounds (400 per gun).

P-51s in film

- Ladies Courageous (1944), starring Loretta Young, the fictionalized story of the Women's Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron depicts a unit of female pilots during WW2 who primarily flew bombers from the factories to their final destinations. Reissued as Fury in the Sky, has early-model P-51As used mainly as backdrops.

- Fighter Squadron, (1948), depicted a P-47 unit based loosely on the 4th Fighter Group (sometimes known as "Blakeslee's Bachelors"). The 4th FG flew P-47s in combat from April 1943 to March 1944, when they converted to Mustangs. In this film, the German Bf 109s are actually painted P-51s. Much of what was depicted with the P-47s (e.g. the fighter escorts going all the way to Berlin, one pilot bailing out over enemy territory and his buddy landing to pick him up) actually happened with P-51s in real life.

- Dragonfly Squadron (1953): B-movie flick of Korean War flyers featuring the P-51.

- Battle Hymn (1956), is based on the real-life experiences of Lt Col Dean E. Hess (played by Rock Hudson) and his cadre of US Air Force instructors in the early days of the Korean War, training the pilots of the Republic of Korea Air Force and leading them in their baptism of fire in F-51D/Ks.

- Lady Takes a Flyer (1958), features a P-51D prominently in the final sequence when Lana Turner (as Magie Colby) crashes dramatically at the end of a perilous ferry flight to England.

- Cloud Dancer (1980): a melodramatic tale of aerobatic flyers includes aerial sequences with a P-51.

- Empire of the Sun (1987): the Steven Spielberg film features a flight of three P-51Ds in a spectacular attack that destroys the Japanese airbase near Soochow Creek Interment Camp, wartime home to the story's protagonist, Jim Graham, played by Christian Bale.

- Memphis Belle (1990): Based on the acclaimed Second World War documentary, the crew of the Memphis Belle, a B-17 bomber, have to make one final bombing raid over Europe before they complete their 25th mission and are able to return home. Five P-51D Mustangs serve as escorting fighters although they were not in the European theatre during the actual mission.

- Tuskegee Airmen (1995): The story of how a group of African American pilots overcame racist opposition to become one of the finest US fighter groups in World War II, utilizes the P-51 as their primary mount although the 99th Squadron would have used P-39s during their North African stint.

- Saving Private Ryan (1998): in Spielberg's film, two P-51Ds, engaged in the destruction of German Tiger I tanks, dramatically appear briefly at the end of the final battle in the fictional French town of Ramelle.

- Spielberg's television miniseries "Band of Brothers" (2001) also features the P-51.

- Hart's War (2002) includes two major scenes involving P-51s, one in which a German train carrying American Prisoners of War (while not properly marked) is strafed by P-51s, and in a dogfight between a 332nd Fighter Group P-51 and a Bf 109 over the Prisoner of War Camp.

References

- Angelucci, Enzo and Bowers, Peter. The American Fighter: The Definitive Guide to American Fighter Aircraft from 1917 to the Present. New York: Orion Books, 1985. ISBN 0-517-56588-9.

- Birch, David. Rolls-Royce and the Mustang. Derby, UK: Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust, 1987. ISBN 0-9511710-0-3.

- Carson, Leonard "Kit." Pursue & Destroy. Granada Hills, California: Sentry Books INc., 1978. ISBN 0-913194-05-0.

- Delve, Ken. The Mustang Story. London: Cassell & Co., 1999. ISBN 1-85409-259-6.

- Ethell, Jeffrey L. P-51 Mustang: In Color Photos from World War II and Korea. St. Paul, Minnesota: Motorbooks International Publishers & Wholesalers, 1993. ISBN 0-87938-818-8.

- Grant, William Newby. P-51 Mustang. London: Bison Books, 1980. ISBN 0-89009-320-2.

- Green, William and Swanborough, G. The Great Book of Fighters. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing, 2001. ISBN 0-7603-1194-3.

- Gunston, Bill. North American P-51 Mustang. New York: Gallery Books, 1990. ISBN 0-8317-14026.

- Hess, William N. Fighting Mustang: The Chronicle of the P-51. New York: Doubleday and Company, 1970. ISBN 0-912173-04-1.

- Jane, Fred T. "The North American Mustang." Jane’s Fighting Aircraft of World War II. London: Studio, 1946. ISBN 1-85170-493-0.

- Jerram, Michael F. P51 Mustang. Yeovil, UK: Winchmore Publishing Services Ltd., 1984, ISBN 0-85429-423-6.

- Johnsen, Frederick A. North American P-51 Mustang. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press Publishers and Wholesalers, 1996. ISBN 0-933424-68-X.

- Knaack, Marcelle Size. Encyclopedia of US Air Force Aircraft and Missile Systems: Volume 1 Post-World War II Fighters 1945-1973. Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History, 1978. ISBN 0-912799-59-5.

- Loftin, LK, Jr. Quest for Performance: The Evolution of Modern Aircraft. NASA SP-468. [9]. Access date: 22 April 2006.

- Mietelski, Michał, Samolot myśliwski Mustang Mk. I-III wyd. I. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Ministerstwa Obrony Narodowej, 1981. ISBN 83-11-06604-3.

- O'Leary, Michael. USAAF fighters of World War Two. New York: Sterling Publishing Co., 1986. ISBN 0-7137-1839-0.

- White, Graham. Allied Aircraft Piston Engines of World War II. Warrendale, Pennsylvania: Society for Automotive Engineers, 1995. ISBN 1-56091-655-9.

- Scramble.nl

External links

- The North American P-51 Mustang

- P51Pilots.com -- P-51 Pilot Biographies, Pilot Stories, Photo Gallery

- Mustang!

- North American P-51 Mustang at Greg Goebel's AIR VECTORS

- North American P-51H Mustang

- P-51 Mustang at American Aces of WW2

- Commemorative Air Force page on P-51 background, history, specs

- Warbird Alley: P-51 page - Information about P-51 Mustangs still flying today

- USAAF Resource Center - P-51 profile

- Warbird Registry - P-51 Warbirds

- List of 284 known surviving Mustangs

- Air Show Photos

- Cuban F-51 Mustangs

Related content

Related development

Comparable aircraft

Designation sequence

XP-48 -

XP-49 -

XP-50 -

P-51 -

XP-52 -

XP-53 -

XP-54

Related lists

Lists relating to aviation | |

|---|---|

| General | Timeline of aviation · Aircraft · Aircraft manufacturers · Aircraft engines · Aircraft engine manufacturers · Airports · Airlines |

| Military | Air forces · Aircraft weapons · Missiles · Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) · Experimental aircraft |

| Notable incidents and accidents | Military aviation · Airliners · General aviation · Famous aviation-related deaths |

| Records | Flight airspeed record · Flight distance record · Flight altitude record · Flight endurance record · Most produced aircraft |

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

cs:P-51 Mustang de:North American P-51 es:P-51 Mustang fa:پ-۵۱ ماستنگ fr:North American P-51 Mustang gl:P-51 Mustang ko:노스아메리칸 P-51 무스탕 it:North American P-51 Mustang he:P-51 מוסטנג nl:P-51 Mustang ja:P-51 (航空機) no:North American P-51 Mustang pl:North American P-51 Mustang pt:P-51 Mustang ru:North American P-51 Mustang fi:North American P-51 Mustang sv:North American P-51 Mustang tr:P-51 Mustang zh:P-51野馬戰鬥機