PlaneSpottingWorld welcomes all new members! Please gives your ideas at the Terminal.

CH-124 Sea King

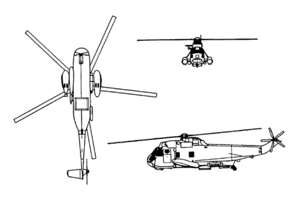

| CH-124 Sea King | |

|---|---|

| A Canadian Navy CH-124 Sea King | |

| Type | ASW / utility helicopter |

| Manufacturer | Sikorsky Aircraft United Aircraft of Canada (assembly) |

| Status | Active service |

| Primary users | Royal Canadian Navy Canadian Forces |

| Developed from | SH-3 Sea King |

| Variants | Westland Sea King |

The Sikorsky CH-124 Sea King is a twin-engined anti-submarine warfare (ASW) helicopter. Based on the US Navy's SH-3, it serves with the Canadian Forces.

Contents

Development

The Royal Canadian Navy was authorized to purchase 41 Sea King models in 1963, designating them CHSS-2 Sea King.[1]

The airframe components were made by Sikorsky in Connecticut but most CHSS-2s were assembled in Montreal by United Aircraft of Canada (now Pratt & Whitney Canada), a subsidiary of Sikorsky's parent company. Upon the unification of Canada’s military in 1968, the CHSS-2 was re-designated CH-124.[1]

Design

The RCN developed a technique for landing the huge helicopters on small ship decks, using a 'hauldown' winch (called a 'Beartrap'),[2] earning aircrews the nickname of 'Crazy Canucks'.[3] The 'Beartrap' allows the Sea King to land on ships that allows recovery of the Sea King in virtually any sea state.[1] In 1968, the RCN, Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and Canadian Army unified to form the Canadian Forces; air units were dispersed throughout the new force structure until Air Command (AIRCOM) was created in 1975.

Operational service

The Sea King is assigned to destroyers, patrol frigates, and replenishment ships as a means of extending the surveillance capabilities of a ship beyond the horizon. When deployed, the Sea King is accompanied by a number of crews - each with 2 pilots, a Tactical Coordinator (TACCO), and an Airborne Electronic Sensor Operator (AESOp).[4]

In order to find submarines, the Sea King's sonar uses a transducer ball at the end of a 450-foot cable. It can also be fitted with FLIR (Forward Looking Infra-Red) to find surface vessels in the dark of night.

The Sea King has undergone numerous refits and upgrades, especially with regard to the electronics, main gearboxes and engines, surface-search radar, secure cargo and passenger carrying capabilities.

Replacement

In 1983, the Department of National Defence began issuing contracts for the Sea King Replacement Project. However, the contracts were not intended to replace the Sea King, then reaching its 20th birthday in Canadian Forces service, but instead were meant to develop new avionics for a unknown new helicopter type to replace the Sea King in CF service.[5]

However, by the mid-1980's, the Canadian Forces slowly started to regard the Sea Kings' as being too small for its intended anti-submarine warfare role due to the ever increasing size and amount of anti-submarine warfare gear that were being required.[6] As such, the New Shipboard Aircraft Project was initiated by the Progressive Conservative government led by Brian Mulroney in 1985 to find a replacement for the Sea Kings.[7]

In 1986 the NSA entered its project definition phase – ‘Solicitations of Interest’ from industry were requested in April 1986. Three contenders were singled out as possible replacement for the Sea King: Sikorsky's S-70 SeaHawk (called the SH-60 Seahawk in the US Navy), Aérospatiale’s AS332F Super Puma and finally, AgustaWestland's new EH-101, of which the latter was purposely designed to be a Sea King replacement[8]

However, in a surprise move, Sikorsky then withdrew from the contest, the reason being that the SeaHawk was seen by the CF to be too small, and furthermore the Sikorsky was competing with its own interests, having bought part of troubled Westland Helicopters, which was offering the EH-101.[9] Aérospatiale in the middle of the contest then tipped its hand by suddenly redubbing its offering as the AS532 Cougar. Many considered the rebranding a previously successful product smacks of desperation, as sales of the AS332F were anything but brisk at the time.[10]

In 1987, the Mulroney government announced the purchase of 35 EH-101 helicopters to replace the CH-124 Sea King. However, by the end of the 1980s, the CF had another problem at its hands; the fleet of CH-113 Labrador search-and-rescue helicopters needed replacing. In 1991, the Mulroney government tacked on CH-113 Labrador replacement to the purchase, in effect merging the New Shipboard Aircraft Project and the New SAR Helicopter Project. Such a move had economic benefits including the lower unit price per aircraft and for spare parts which accompany larger orders. The training of maintenance personnel and flight crews is simplified, and staffing headaches reduced. However, such a move also increased the total costs of the program; now up to $5.8 billion dollars Canadian for 50 helicopters (broken down into 35 ASW Sea King replacements and 15 SAR types, dubbed CH-148 Petrel for the former, and CH-149 Chimo for the latter).[11] However, the country at the time was in no position to be spending billions of dollars, as the government was facing a mounting deficit, and growing unemployment. In 1993, the new leader of the Progressive Conservative Party, Kim Campbell, in an attempt to deflect mounting criticism from the population over the unexpectedly large purchase price announced that the actual order was being reduced to 28 Petrels and 15 Chimos, reducing the purchase price down to $4.4 billion dollars.[12] However, the political damage was done, and it did not help Tory creditability that when Campbell suggested that an ASW capability could be vital if submarines were used to run the blockade of Haiti, as the very idea that submarines might run this blockade in support of the Haitian junta was absurd.[13] The Liberal leader, Jean Chrétien then the leader of the Opposition, had disparagingly referred to the EH-101 as a 'Cadillac' during a time of government restraint and deficit fighting.[14]

However, following a change of government in October 1993, the incoming Liberal Party ordered the Canadian Forces to immediately cancel the entire order, forcing the payment of cancellation fees of $500 million (CAD). By cancelling the project and slashing the DND budget, the government hoped to trim the deficit and become more fiscally responsible. But by canceling the New Shipboard Aircraft Project outright, the new Liberal government left itself with very little room to maneuver, as during the 1990s the Sea Kings' air frames, engines and avionics systems slowly but steadily became dated and obsolete as the Sea King entered its 30th year of service. The Sea Kings still needed replacing, but no alternative or contingency plan was offered. Some have noted that the decision to simply cancel the NSA contract in the end did not turn out to be very fiscally responsible of the government at the time.[15]

However, events unfolded to force the government's hand on the matter. By the mid 1990s each Sea King requires over 30 man-hours of maintenance for every hour of flying time, a figure described by the Canadian Naval Officers Association as 'grossly disproportionate'.[16] Furthermore, the helicopters are unavailable for operations 40% of the time and due to the fact that the airframes are 10-15 years older than other Sea Kings flying in allied air forces, AIRCOM is frequently forced to have spare parts custom-made as Sikorsky's supplies are either overly expensive or no longer exist. AIRCOM's Sea Kings are now widely perceived as unreliable, outdated and expensive to maintain, by observers both inside and outside the Canadian Forces. In late 2003, the entire fleet was grounded (except for essential operations) for several weeks after two aircraft coincidentally lost power within a few days of each other.

When it subsequently became clear that new helicopters were still desperately needed to replace AIRCOM's CH-124 Sea King fleet, the Liberal government began a slow, tortured procurement process that critics have accused of being deliberately tailored to prevent the EH-101 from being chosen as a candidate. One problem was that the government continued to tweak the terms of the new Sea King replacement project, dubbed the Maritime Helicopter Project. The project was divided into two sections, with distinct airframe and integrated mission systems components. The two-parts decision was attacked from all sides; opponents insisted that separating the major MHP components would only serve to drive up total costs.[17] Public Works insistence on “lowest-cost compliant” bids did not help the situation any further.[18]

Candidates to the new Maritime Helicopter Project consisted of Sikorsky's S-92 Superhawk, NHIndustries NH-90, and finally, AgustaWestland's EH-101.[19]

In December 2002, the new Minister of National Defence, John McCallum, reversed that ill-considered ‘two-part’ approach, deciding “to proceed with a single contract rather than two”. However, this decision was criticized again, by the same industry types and defence pundits who had attacked the earlier decision to split the MHP contest into separate airframe and integrated mission systems parts.[20]

The Liberal government continued the leisurely pace of the project despite several high profile and embarrassing Sea King crashes. It soon became clear the that policy-makers were waiting for Jean Chrétien to retire. However, until December 2003, the only question was: who would last longer. When Chrétien finally retired in December 2003, the new Prime Minister, Paul Martin, made replacing the Sea Kings a top priority within the DND. A spending freeze was applied to all other major DND projects, except for the Maritime Helicopter Project. Furthermore, tenders were being issued on December 17, 2003 for a selection of a Sea King replacement.[21]

Suddenly, the DND then decided to that the NH-90 was “non compliant” with their MHP requirement and this helicopter was eliminated from the contest, despite rumours that the NH-90 had all but won the contest a few months ago. The NH-90’s apparent reversal of favour might also be seen as being politically motivated, as Canada was keen on improving industrial relations with France. Other factors indicated that the DND had valid reasons of its own to reject the NH-90 – size, which had influenced the project from the outset.[22]

Finally, in July 2004, it was announced that the Sea Kings will be replaced by the new Sikorsky H-92 Superhawk, carrying a General Dynamics mission package, with the first of 28 CH-148 Cyclones scheduled for delivery in 2008.

Variants

- CH-124

- Anti-submarine warfare helicopter for the Royal Canadian Navy (41 assembled by United Aircraft of Canada).[1]

- CH-124A

- The Sea King Improvement Program (SKIP) added modernized avionics as well as improved safety features.[1]

- CH-124B

- Alternate version of the CH-124A without a dipping sonar but with a MAD sensor and additional storage for deployable stores.[1]

- CH-124B2

- 6 CH-124B's were upgraded to the CH-124B2 standard in 1991-1992. The revised CH-124B2 retained the sonobuoy processing gear to passively detect submarines but, the aircraft was now also fitted with a towed-array sonar to supplement the ship's sonar. Since anti-submarine warfare is no longer a major priority within the Canadian Forces, the CH-124B2 were refitted again to become improvised troop carriers for the newly formed Standing Contingency Task Force.[1]

- CH-124C

- One CH-124 operated by the Helicopter Operational Test and Evaluation Facility located at CFB Shearwater. Used for testing new gear, and when not testing new gear, it is deployable to any Canadian Forces ship requiring a helicopter.[1]

- CH-124U

- Unofficial designation for 4 CH-124's that were modified for passenger/freight transport. One crashed in 1973, and the survivors were later refitted to become CH-124A's.[1]

Operators

Specifications (CH-124 Sea King)

General characteristics

- Crew: 4 (2 pilots, 1 navigator, 1 airborne electronic sensor operator)

- Capacity: 3 passengers

- Length: 54 ft 9 in (16.7 m)

- Rotor diameter: 62 ft (19 m)

- Height: 16 ft 10 in (5.13 m)

- Disc area: ft² (m²)

- Empty weight: 11,865 lb (5,382 kg)

- Loaded weight: 18,626 lb (8,449 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 22,050 lb (10,000 kg)

- Powerplant: 2× General Electric T58-GE-8F/-100 turboshafts, 1,500 shp (kW) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 166 mph (267 km/h)

- Range: 621 mi (1,000 km)

- Service ceiling: 14,700 ft (4,481 m)

- Rate of climb: 1,310-2,220 ft/min (400-670 m/min)

Armament

- 2× Mk 46 Mod V anti-submarine torpedoes

- Various sonobouys and pyrotechnic devices

- door guns (some variants)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 CH-124 Sea King Variants. Canadian American Strategic Review. Retrieved on 2007-06-19.

- ↑ Haze Gray & Underway - The Canadian Navy of Yesterday & Today - Sea King.

- ↑ CBC News In Depth: Canada's Military.

- ↑ Canada's Air Force - Aircraft - CH-124 Sea King - Technical Specifications.

- ↑ CASR: Politics, Procurement Practices, and Procrastination: the Quarter-Century Sea King Helicopter Replacement Saga - Part 3.

- ↑ CASR: Politics, Procurement Practices, and Procrastination: the Quarter-Century Sea King Helicopter Replacement Saga - Part 4.

- ↑ CASR: Politics, Procurement Practices, and Procrastination: the Quarter-Century Sea King Helicopter Replacement Saga - Part 4.

- ↑ CASR: Politics, Procurement Practices, and Procrastination: the Quarter-Century Sea King Helicopter Replacement Saga - Part 5.

- ↑ CASR: Politics, Procurement Practices, and Procrastination: the Quarter-Century Sea King Helicopter Replacement Saga - Part 7.

- ↑ CASR: Politics, Procurement Practices, and Procrastination: the Quarter-Century Sea King Helicopter Replacement Saga - Part 8.

- ↑ CASR: Politics, Procurement Practices, and Procrastination: the Quarter-Century Sea King Helicopter Replacement Saga - Part 9.

- ↑ CASR: Politics, Procurement Practices, and Procrastination: the Quarter-Century Sea King Helicopter Replacement Saga - Part 10.

- ↑ CASR: Politics, Procurement Practices, and Procrastination: the Quarter-Century Sea King Helicopter Replacement Saga - Part 10.

- ↑ CBC News In Depth: Canada's Military.

- ↑ CASR: Politics, Procurement Practices, and Procrastination: the Quarter-Century Sea King Helicopter Replacement Saga - Part 13.

- ↑ http://www.naval.ca/article/myrhaugen/seakingreplacement_byleemyrhaugen.html

- ↑ CASR: Politics, Procurement Practices, and Procrastination: the Quarter-Century Sea King Helicopter Replacement Saga - Part 14.

- ↑ CASR: Politics, Procurement Practices, and Procrastination: the Quarter-Century Sea King Helicopter Replacement Saga - Part 15.

- ↑ CASR: Politics, Procurement Practices, and Procrastination: the Quarter-Century Sea King Helicopter Replacement Saga - Part 15.

- ↑ CASR: Politics, Procurement Practices, and Procrastination: the Quarter-Century Sea King Helicopter Replacement Saga - Part 16.

- ↑ CASR: Politics, Procurement Practices, and Procrastination: the Quarter-Century Sea King Helicopter Replacement Saga - Part 16.

- ↑ CASR: Politics, Procurement Practices, and Procrastination: the Quarter-Century Sea King Helicopter Replacement Saga - Part 16.

External links

Related content

Related development

Designation sequence

- - CH-124 -

Related lists

Template:Sikorsky Aircraft Template:CF aircraft

Lists relating to aviation | |

|---|---|

| General | Timeline of aviation · Aircraft · Aircraft manufacturers · Aircraft engines · Aircraft engine manufacturers · Airports · Airlines |

| Military | Air forces · Aircraft weapons · Missiles · Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) · Experimental aircraft |

| Notable incidents and accidents | Military aviation · Airliners · General aviation · Famous aviation-related deaths |

| Records | Flight airspeed record · Flight distance record · Flight altitude record · Flight endurance record · Most produced aircraft |